In traditional Japanese tea ceremonies, there are two styles in which matcha is prepared – Usucha and Koicha. Usucha, literally translated as ‘thin tea’, refers to a thin, or light, preparation of matcha — the version we see most commonly prepared. Koicha, literally translated as ‘thick tea’, refers to a style of matcha preparation that is much more concentrated than usucha, and is traditionally prepared as a communal drink during a tea ceremony to be shared among the guests. In general, koicha is usually reserved for special occasions whereas usucha is more of a day-to-day preparation.

Matcha-making has long been considered an art form. In fact, it dates back to the olden days of the Japanese tea ceremonies where each step of matcha preparation was strictly choreographed into a series of intricate meditative movements. Despite matcha’s fascinating history, its context and preparation method can come across as intimidating to many. Thus, it is our goal to make matcha more accessible and relevant to today’s modern lifestyle.

Matcha is derived from the same tea plant as all other types of teas — camellia sinensis, whose leaves can be made into green, white, yellow, oolong, black and pu-erh tea. Matcha belongs to the Japanese green tea category, meaning that it’s steamed after being harvested to stop the oxidation process — hence the reason why it retains its brilliant green colour. What makes matcha truly special is its growing style, harvest and production process. It is the conditions under which matcha is grown and produced that contribute to its unique colour, aroma and taste profile.

‘Terroir’ is a French term that refers to the natural environment that influences the characteristics of a crop – an expression most commonly associated with wine. It encompasses all the natural factors of the surroundings – including geography, altitude, climate and soil. The notion of terroir, however, is extremely important when it comes to growing exceptional matcha, as it defines all the environmental factors that influence the characteristics of the tea.

Matcha can be classified into two broad grades: Ceremonial Matcha, which generally describes matcha grades appropriate for use in traditional tea ceremonies, and Culinary Matcha, which describes matcha grades suitable for use as an ingredient in drink or dessert recipes. Parallel to the world of wine, ceremonial matcha can be compared to fine, drinking wine while culinary matcha can be compared to cooking wine.

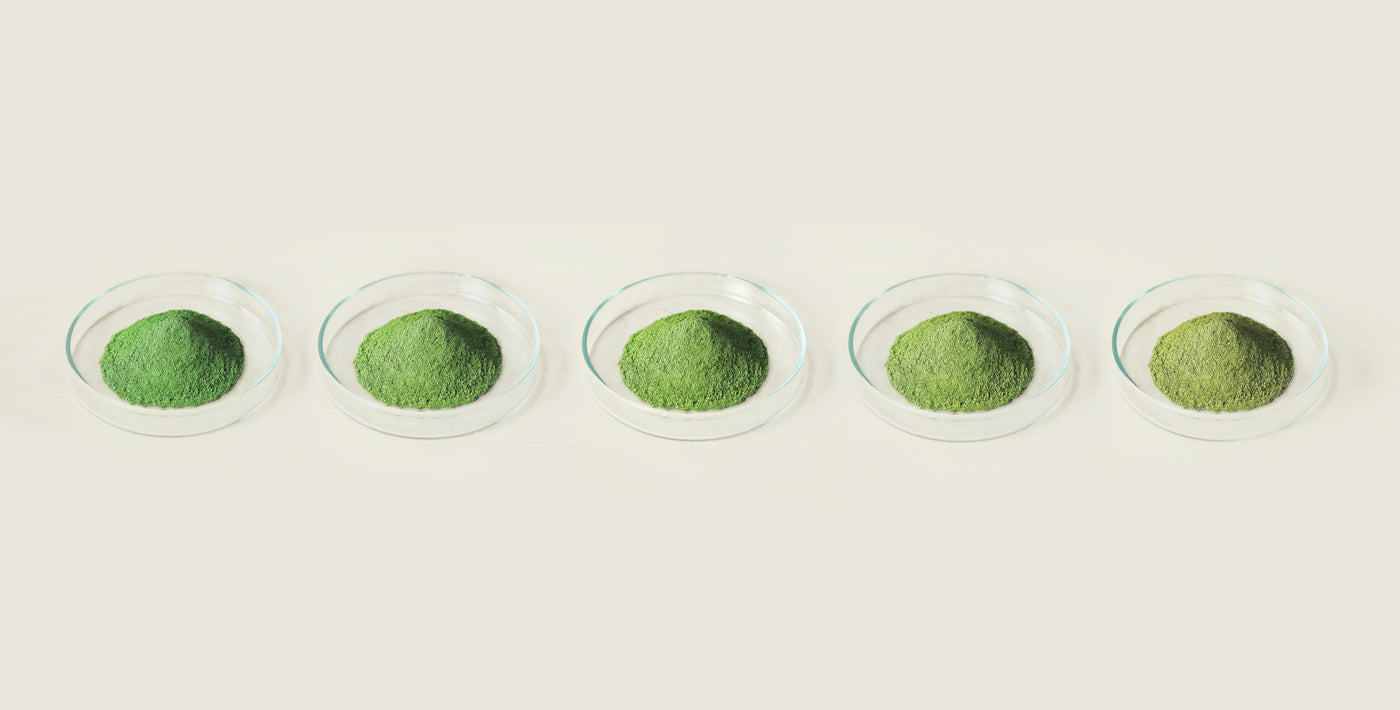

Like fine wine, matcha comes in a broad quality spectrum. While it’s not typically easy to determine the matcha quality simply by looking at the label alone, there are four main “sensory cues” one can use to assess the quality of matcha: colour, texture, aromas, and taste.

Drinking the finest grades of matcha provides an epicurean experience not unlike that of the finest wine. These two highly-prized drinks with a long history of its own bear a great deal of similarity not only in terms of the high level of expertise and the tremendous efforts required in the production process, but also the breadth and depth of their flavour profiles. The paralleled nature of these two beverages makes it a compelling case why the finest grades of matcha should demand the same level of respect and appreciation as that of a truly great wine.

As the most consumed beverage in the world after water, tea has a long and complex history that spans multiple cultures over thousands of years. Matcha has evolved through a fascinating journey that first began in China, and continued via the spread of Zen Buddhism to Japan before it was later assimilated as the centrepiece of the Japanese tea ceremony. Now it has attained global popularity to become one of most unique and highly-prized delicacies of the 21st century.